Explorer’s Valley

Explorer’s Valley follows a river where we now find footprints of bears and deer. How do paleontologists find fossils in a forest landscape? How does ancient life help us understand the biodiversity we see around us today?

Questions to keep in mind

- Can you spot a fossil in the middle of a forest?

- Can you see the same sorts of life as we see in fossils?

- What about dinosaur descendants?

Tyrannosaurs

You've heard of Tyrannosaurus rex, but tyrannosaurs are a big family of meat-eating, two-legged dinosaurs that lived during the Cretaceous Period.

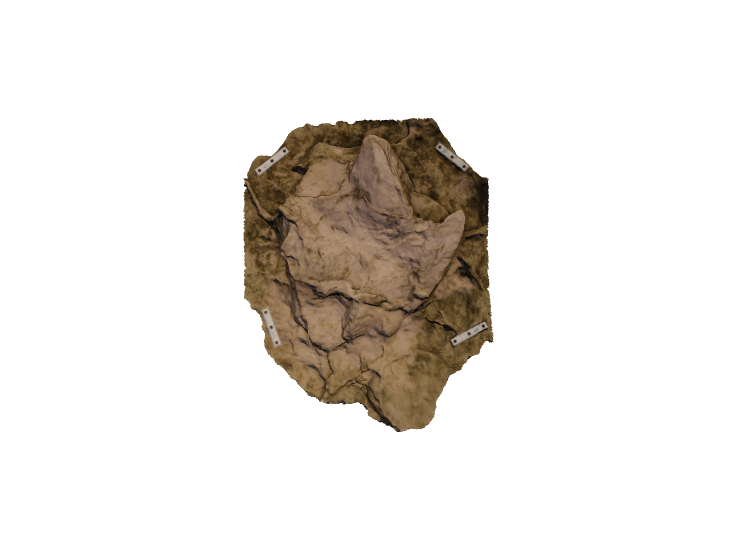

Spot the footprint

Finding a tyrannosaur footprint is a big deal. Lisa has very sharp eyes. Can you make out the footprint?

Point of view - Richard looks up a rocky hill at Lisa.

Lisa: There might be something that wants to be a footprint.

Richard looks down at a large piece of rock. Toe-shaped bumps protrude from the rocks surface.

Richard: So this might possibly be a footprint there. This is a toe, another toe, and another toe. I think it’s not bad actually.

Richard traces his finger along the outside of the footprint pointing out the three visible toes.

Richard: So one, two, three, this one’s diverging. So it makes it two, three, and four. It probably is a print, just really, really beaten up.

Lisa: Oh yeah, well took a bit of a tumble.

Richard brushes off some of the loose rock around the footprint.

Richard: I’d say this looks like a tyrannosaur print too. Yeah, I’d buy that for a tyrannosaur print. So just added another to a very rare amount of them in the world; there’s less than 20.

Same or different?

This scan is of another tyrannosaur footprint found by Richard. Does it look the same as the one in the video?

We're sorry! 3D content is only available when Javascript is enabled.

to explore

in and out

What made the footprint?

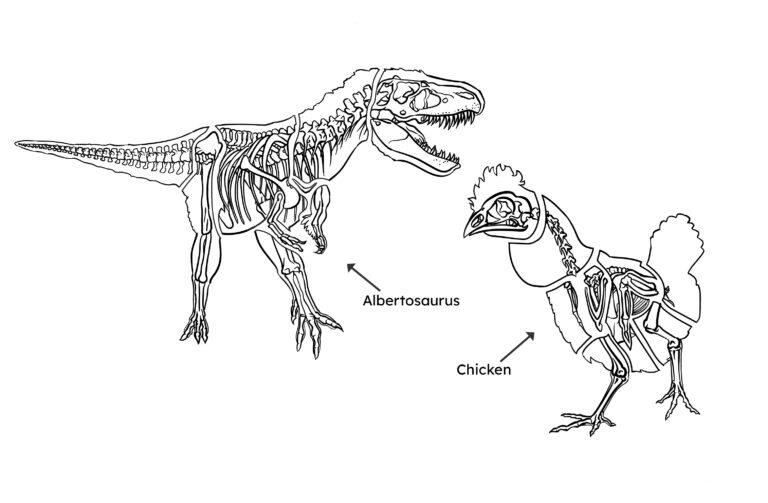

The Albertosaurus is a type of tyrannosaur from the later Cretaceous Period. It was found in Alberta and grew up to 10 metres long. Could it be similar to the dinosaur that made the footprint?

We're sorry! 3D content is only available when Javascript is enabled.

to explore

in and out

How big were these dinosaurs?

Tomorrow's fossils?

Modern animals leave behind footprints on the wet ground near the river. Footprints give clues to an animal's behaviour. What were they doing?

Look familiar?

How do Lisa and Richard know which animals made these prints? What is similar about how they identify dinosaurs from their footprints?

Lisa looks down at some tracks in the mud.

Richard: Probably the little black bear. The difference between black bear and grizzly bear tracks is, and well these are old so it’d be tough to tell anyways, but the black bear while it kind of looks like that

Richard looks down at the track and points it out with his hiking pole.

Richard: —you don’t see any claw marks—but with the grizzly you always see claw marks or almost always see claw marks right out in front of the digital pads.

A clear impression of a black bear paw in the mud. The toe tips are rounded.

Two grizzly bear tracks in dry mud. The toe tips are pointed.

Richard: Okay, so we have some deer tracks here. Little tiny ungulates. That’s a small deer and then this could be elk maybe but not very… Very old [tracks].

Richard looks down at the muddy river bank and points out hoof impressions.

Future fossil?

If conditions are exactly right, this bear footprint could turn into a fossil over millions of years. What would we be able to tell about bears from this fossil?

A moose was here

What would you be able to describe about moose from their footprints?

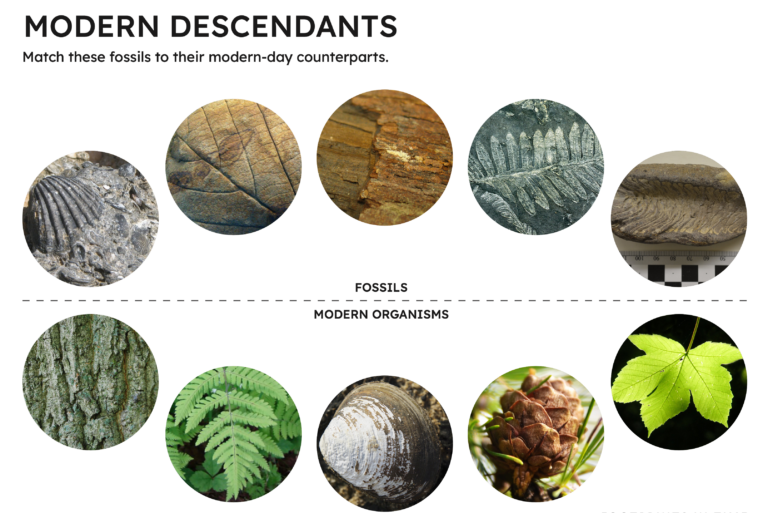

Modern descendants

Birds are dinosaurs

Some dinosaurs had bird-like features. We used to think that all dinosaurs died out, but in fact, some survived and evolved into modern birds.

Living dinosaurs

Birds are the only descendants of dinosaurs to live past the end of the Cretaceous Period. Their small size probably helped them survive. How big are these sandpiper footprints compared to dinosaur footprints?

Lisa looks down at some markings in the muddy riverbed. She raises her hands in excitement.

Lisa: Spotted sandpiper!

Richard: Oh, Okay!

Lisa points out the straight line of probe marks in the mud with her hiking pole.

Lisa: Little probe marks.

Richard: Oh, look at that. So, bill probe marks as the as the spotted sandpiper was walking along the the little puddles here looking for some kind of invertebrates, I guess.

The probe marks move between two murky puddles in the muddy riverbed.

Lisa: The footprints aren’t really good but the probe marks are nice.

Richard: So all these in here.

Lisa: We can do better. But they’re here.

Richard: They are here.

Birds are still evolving

Darren Irwin, Professor of Zoology at UBC, studies birds where Richard and Lisa found the dinosaur footprints. What similarities does he point out between birds and dinosaurs?

A fossil replica of a bird-like creature. Its feathered wings are outstretched and its neck is bent back into an awkward position.

Darren: So Archaeopteryx was clearly recognized as a bird when it was discovered, mainly because of the clear wings with flight feathers, asymmetric feathers, on it.

Close up of the wings. They are outlined with a white overlay.

Darren: And so this was clearly a flying reptile and provided the link between reptiles and birds. So modern birds and theropod dinosaurs share a lot of features.

Birds fly together in a large group.

Darren: And it’s increasingly recognized that dinosaurs, rather than being these cold-blooded, slow-moving animals that we used to think of them as, were really probably endothermic, meaning warm-blooded, they have good parental care, they had a lot of colourful feathers on them. And they had a lot of displays. They probably made calls in a lot of mating displays and so forth. All those traits are very similar to modern birds.

A grey-haired man in a green jacket looks at the camera.

Darren: My name is Darren Irwin. I’m a professor here at the UBC Biodiversity Research Centre. And I study bird speciation, so how one species gradually becomes two over time.

A bird’s-eye view

Watch this fly-through of the river valley. How would this landscape have looked different during the Cretaceous Period?

Spot the similarities

Duck-billed dinosaurs

Hadrosaurs are crested dinosaurs. No one knows for sure why they had crests on their heads, but some paleontologists think it was for making noises.

A splash in time

We know from fossils that hadrosaurs, like this Corythosaurus, lived here. How do you think they interacted with their environment?

Hide and seek

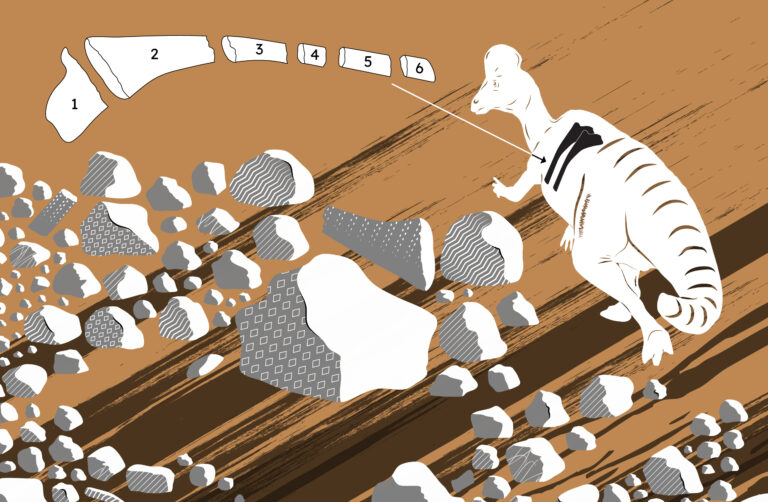

Richard was able to find this bone among all the rocks by the river. Could you spot the bone before him?

Text: Can you spot the piece of bone?

Point of view – Richard looks down a hill. Loose rock debris is scattered all over. Tufts of long grass poke up between the debris. Richard leans in and picks up a piece of rock that is browner than the surrounding rock.

Richard: Found a bit of a rib!

Richard picks up a few more pieces of rock and examines them.

Richard: So this would be part of a long bone, cuts through right there. They’d have to clean it up, but this is all bone right here. And this is sediment that’s adhering to it. See?

Richard pulls off some flakes of rock attached to the bone.

Richard: Decent chunk of bone. There’s another chunk of bone here, it came from the same rock. Might be the head of a rib, possibly. See, expands that way.

Richard traces his finger along the bone outlining its shape.

Richard: Came from that way. So we have to find a way to get there. But that doesn’t mean that there’s going to be more.

Richard looks up the hill. There are more rocks and trees above.

Hadrosaur fossils

These hadrosaur footprints were found on a different expedition. The toes are wider and more rounded than the tyrannosaur footprint.

Finding fragments

Geo facts | Glaciers are cool

Even though they have long since melted, we can tell that glaciers once filled this valley from the clues they left behind. What are some of the signs of past glacial activity?

Glacial till

One way you can tell that there were glaciers here is the sediment they left behind. Glacial erosion creates a distinct form of sediment called till.

Point of View - Richard looks up a hill. He points out a layer of grey sediment that contains rocks of all sizes. The grey sediment sits on top of a different layer of brown sedimentary rock.

Richard: You see all that unconsolidated lots of boulder, lots of mud, sand, etc. from there up is all up until the soil horizon which is right below the tree roots just well, actually even the tree roots are it, this is all glacial till from the last ice age, Wisconsin ice age, about 10 to 14,000 years ago.

A graphic showing the top half of North America covered by a glacier is shown. Richard points to the brown layer of rock below the glacial till.

Richard: But this level here is the 70, about 74 million year old Wapiti Formation. And these rocks are part of it as well. So that's the situation. 74 million year old rocks overlain by a 14,000 year old glacial, unstratified glacial till.

Lisa: In geology speak we call that an unconformity.

Valley shapes

A valley’s shape can tell you how it was formed. This valley’s shape tells us that it was once filled with glaciers.

Drone footage of several different valleys of different shapes and sizes.

Sam: What gives a valley its shape? There are two main ways that valleys form. Rivers in high mountains move very fast and have a lot of power to erode rock. Usually these rivers are very skinny and this results in a V-shaped valley with a narrow bottom and straight steep sides.

A steep sided V-shaped valley with a skinny river running through it.

Sam: When the planet gets colder, glaciers flow down from mountains like giant rivers of ice. The wide base of the glacier scrapes away the rock underneath. When the planet warms and the glaciers melt, it leaves behind a U-shaped valley with a wide base and curving sides.

A wide U-shaped valley with a wide river running through it. An image of a glacier fades in and fills the valley.

Sediment recycling

Where glaciers once carved out this valley, a river now continues the process. Glacial till becomes new deposits as it is carried downstream.

Drone footage flying through a wide U-shaped valley. The sides of the valley are covered in conifers. A wide rocky river runs through the valley.

Sam: Not every deposit survives long enough to become rock. Sometimes one sedimentary deposit will get recycled or broken up into pieces that are deposited again in a new setting. Here we see a modern river that passes through an ancient glacial valley. The valley was once full of glacial till deposits. Today, the river breaks up those till deposits, moves them downstream, and then redeposits them as river sediments.