Dinosaur Peak

High in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, you discover hundreds of fossil footprints. From shells and other clues in the rock, we know the footprints were made 135 million years ago. This was during the early Cretaceous Period, in the age of dinosaurs!

Questions to keep in mind

- How did the footprints get here?

- What kinds of dinosaurs made them?

- What do you need to study these fossils?

Dinosaurs walked here

You discover hundreds of dinosaur footprints on the mountain. Some of them line up in a trail called a trackway. What dinosaur could have made them?

Following in the footsteps

Your drone follows the trackways. These footprints came from a nodosaur, a type of ankylosaur. It was walking on flat land, but changes in the earth mean its footprints are now on the side of a mountain.

The camera tracks along an exposed grey stone slab near the top of a mountain peak. A reddish-brown spiky ankylosaur walks on all fours along the slab following fossilized footprints. Its tail sways behind it as it traces the path it would have walked millions of years ago.

Tracing the past

Footprints can be difficult to spot, often they can just look like a bumpy rock. Watch Lisa and Richard trace these footprints. Can you see the toes before they point them out?

Richard: This one there’s no way this isn’t an ankylosaur.

Point of view – Richard looks at a chunk of grey rock with slight depressions on it. Lisa kneels down next to the rock. Richard starts to trace out the outline of a footprint with chalk.

Richard: So, yeah, so there’s that. There’s our footprint and it’s a left footprint of an ankylosaur. And this is, this is big but it’s not as big as some of the ones that I’ve seen here.

The outlined footprint has four rounded toes and is four times the length of Lisa’s hand.

Richard: Looks like there’s a handprint behind it. Ankylosaurs have five toes on their hands. I only see…

Richard starts to trace the outline of a handprint behind the footprint.

Lisa: I’m just getting finger and toe tips.

Richard: Yeah, just…

Lisa: It might be a bit of a depression there.

Richard: That’s it, that is it.

The outlined hand has similarly rounded fingerprints and is about half the size of the footprint.

Close up with an ankylosaur footprint

Footprints can tell us a lot about a dinosaur. The squares on the ruler are one centimetre wide, how big is this footprint? Can you guess how big the ankylosaur was?

Tracking the Trails

Traces of dinosaurs

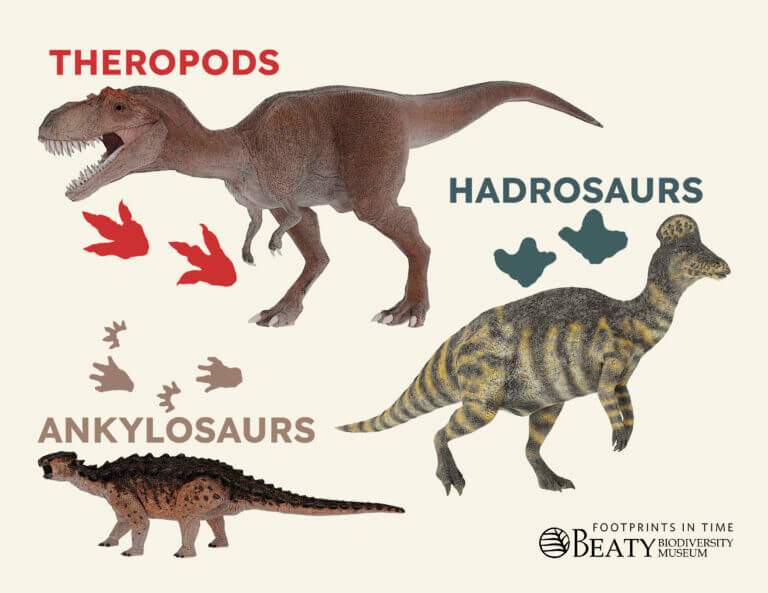

Footprints are trace fossils - traces of dinosaur life that were left behind. They don’t contain bones, but paleontologists guess the dinosaur based on others they know about from a similar time and place.

Counting the claws

Dinosaur footprints with three long toes and sharp claws were probably made by meat-eating dinosaurs called theropods. Can you see the points left by the claws?

We're sorry! 3D content is only available when Javascript is enabled.

to explore

in and out

Similar or different?

Allosaurus is a theropod from an earlier time period. Look at its feet. What do they look like? What would their footprints look like?

We're sorry! 3D content is only available when Javascript is enabled.

to explore

in and out

Recording a find

You can’t take these footprints back with you, so how will you record your find? Richard shares some of his notes. What else do you write down?

Richard sits near a piece of rock that has a theropod footprint outline in chalk on it.

Richard: This is not a track slab that we’re going to collect. We’re not actually collecting anything here, but we can at least take notes about it, and where it is located so that another expedition can find it again. So we get a GPS position...

Richard picks up his handheld GPS.

Richard: and then we make some field notes.

Richard opens his small yellow notebook.

Richard: Do a description of what you found. Of course we always like to know what time things are found.

Richard pulls a pocket watch out of his shirt pocket.

Richard: I’m gonna I make a notation here about the location. Cause you never know down the road who’s going to be interested in in something like this.

Holding his GPS Richard makes a note of the coordinates of the footprint in his notebook.

Fossil impressions

A chocolate cast of a footprint sits on top of a pan of shortbread cookies, a small, red model tyrannosaur skull lies next to the pan.

On an empty wooden surface, ingredients are presented one after another in individual dishes: 1 cup of softened unsalted butter, 1/3 of a cup of granulated sugar, 1 cup of brown sugar, 1 teaspoon of vanilla extract, 1 tablespoon of instant coffee, and 2 cups of flour.

A glass mixing bowl is placed on a wooden table. The butter is mixed with the granulated sugar using a red spatula. Next the brown sugar is mixed in. The vanilla extract is then added to the mix, forming a light brown paste. Finally both the flour and coffee are mixed in, forming a dry, crumbly dough. The cookie dough is poured into a baking pan. The dough is evenly spread in the pan, but it is also kept loose and not tightly packed.

Half a potato has a dinosaur footprint carved out of the cut surface, like a stamp. It is dipped into flour, evenly coating the footprint. The potato is then used to make five footprint impressions on the top of the unbaked shortbread. The pan of shortbread with footprint impressions is put into the oven at 325°F. After 30-40 minutes the cooked shortbread is removed from the oven.

A handful of chocolate chips are poured into a bowl and then melted in the microwave. The top of the shortbread cookies is dusted with cocoa power and the melted chocolate is poured into the footprints. The chocolate has cooled and is gently separated from the cookie with a butter knife. A cast of the footprint is revealed on the underside of the chocolate.

Dinosaur detectives

Who studies dinosaur footprints? Lisa and Richard are paleontologists, scientists who study ancient life from fossils. Join these dinosaur detectives, and don’t forget your camera!

Bring the right equipment

To get to these footprints you have to get up the mountain first. How will you get close enough to study them? You can’t bring the footprints back with you, so how will you record what you see?

Car headlights illuminate a paved road as it drives along in the dark. Dark silhouettes of trees are visible against the sky. A helicopter approaches an airfield as the dawn breaks. From inside the helicopter cockpit looking out, a field stretches into the distance with a single mountain outlined against the light blue sky. Cut to black.

The helicopter flies over a forest towards a mountain range as the morning sun rises just above it. Down below misty clouds gather in the valley between tree-covered mountains. As the helicopter flies further into the mountain range brown rocky peaks poke above the tree line. A woman with a red bandanna and sunglasses (Lisa) sits in the rear of the helicopter surrounded by expedition gear. She smiles and waves.

Even deeper into the mountain range the mountains get taller with sharper peaks. The green valleys reach only a short distance up the base of these rocky giants. The helicopter flies close over a peak, our destination, Richard points a finger at a rock face near the top, next to a glacier remnant. Fade to black.

The helicopter sits in a grassy field with its blades still spinning as it prepares to take off. Mountains stretch along behind it. Walking along a muddy snow melt pool, impressions of bear paws are visible. Lisa with her hiking pack on crouches down and traces her finger across a stone slab. The rocky mountain ridge behind her climbs into the sky.

Looking up, the mountain peak rises far above. Loose rock debris from erosion covers its slopes. Lisa holds a brown rock and points out a fossilized fern visible on its surface. A man dressed in hiking gear (Richard) climbs the loose rocky slope of the mountain. Lisa holds a greyish-brown rock and points out a piece of blue fossilized bone embedded within. She opens a small yellow notebook and begins to write while sitting next to the fossil.

Looking up, the rock slab and glacier remnant that was visible from the helicopter are close. We have reached the top. Looking back down the long slope of the mountain the field the helicopter landed in is visible. Richard sits on the slope of the mountain holding a drone controller. A quadcopter drone takes off into the air in front of him.

Drone point of view: the mountain side covered in debris from erosion slopes down towards the field with the snow melt pool. Tracking along the stone slab on the mountain side, impressions from dinosaur feet are visible on its surface. A stream flows through a mountain valley breaking up the surrounding forest. Two tents are pitched on the hill above. Cut to black.

Safety first

Being a dinosaur detective isn’t easy! You want to get a closer look at these footprints, but climbing a mountain slope can be dangerous. What safety equipment will you need?

Bones can be colourful

You find a piece of dinosaur bone – the first one at this site! As the bone turned to rock, some minerals in this process turned it blue. Lisa and Richard think it came from an animal like a turtle.

Pack your bags

Geo facts | The changing Earth

135 million years ago, the ground here was flat, soft, and wet. Dinosaurs left footprints that were buried and turned to stone deep underground. So why have you found them on the side of this mountain?

Bending stone

Richard points out an area on the mountain to you. Can you see where the rock layers have folded into a wavy shape? How did this happen?

Richard: So looking at these walls, you see that there’s a lot of contortion of the sedimentary beds all of these would have been originally horizontal.

Point of View – Richard looks up at a mountain ridge. Layers of bent and folded rock stand vertically along the ridge.

Richard: And at sea level or below sea level for some of the marine rocks, which are in the area. The dinosaur tracks are in the Gorman Creek Formation, which is a primarily terrestrial formation and about 135 million years old.

Richard walks closer towards the mountain ridge. Rocky debris from erosion is visible on the slopes.

Richard: But in this area, we’ve had a lot of plate tectonic action, which is caused a lot of this folding that you can see. So you see that there’s some beds that are kind of bowed upwards. Those are called anticlines. So they are like a bump.

Richard points at the mountain slope and traces upwards with his finger. Overlayed white lines follow his finger’s path.

Richard: And then then they come down and up again in the depressions are called synclines and back to another anticline and on and on and on, over the whole wall.

Richard traces downwards then upwards again making a wavy path along the mountain slope.

Faults and folds

Faults and folds are two ways rocks deform and create mountains. A fault is a crack that happens quickly. A fold is a bend that happens slowly. They are often connected.

Sam: Tectonic forces press on rocks and cause them to move out of the way or deform. Rocks can deform quickly by cracking. This is called geological faulting.

Animation. Two arrows press on a cross-section of stratified rock. The arrows slowly compress then eventually spring back as then rock cracks down the middle.

Sam: Rocks can also deform slowly by folding. Folds are commonly formed when faults cause rock layers to move out of the way. A fault-bend fold happens when a fault cuts all the way through folded layers. The layers bend as they get pushed over the fault.

Animation. A cross section of stratified rock is split in two by a fault that goes all the way through the top layer. The top section of the rock is slowly pushed up over the fault and bends.

Sam: A fault-propagation fold happens when a fault doesn't cut all the way to the top of the folded layers. This forces the layers on top of the fold to make space for the rock. Moving along the fault underneath.

Animation. A cross section of stratified rock is split by a fault. The fault goes up halfway through the layers. The rock is slowly bent as it is pushed along the fault.

Sam: In Dinosaur Peak, since the faults don't cut all the way to the top, these are probably fault-propagation folds.

An eroded mountain is seen in the distance. Layers of rock are bent with some of them almost vertical.

Sam:Hi, my name is Sam Shekut. I'm a PhD candidate here at the University of British Columbia, where I study sedimentary geology. In my studies, I use the layers of the earth to reconstruct past environments.

Shifting sedimentation

Lisa and Richard found both turtle bones and dinosaur footprints at this site. How did both marine and terrestrial fossils end up in the same place?

Sam: Different types of sedimentary rock get deposited in different places. The location depends on how fast the water is moving and how heavy the sediments are.

Animation. A cross-section of a coastal environment. Rivers run down hill and into the ocean. Sedimentary deposits of different types are outlined.

Sam: In a coastal setting, river sediments are deposited above the shoreline. As you move further from shore the water's movement is slower. Heavier sediments are deposited closer to the shore, while lighter sediments are carried further out.

The sea level starts to decrease and the positions of the deposits move outward with it. Previous deposits remain where they were.

Sam: Over time, as sea levels rise and fall, where these sediments are deposited shifts. This causes different rock types to stack on top of each other. This is called interfingering.

The sea level starts to rise and the positions of the deposits move inward with it. Previous deposits remain where they were.

Sam: This also explains why at Dinosaur Peak there are terrestrial rocks on top of marine rocks.

A shallow sea

North America looked very different in the past. During the time of the dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous, North America was cut in half by a shallow, warm sea that ran from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

Map: Christopher Scotese, CC BY 4.0

We're sorry! 3D content is only available when Javascript is enabled.

to explore

in and out